Discussion points and feedback:

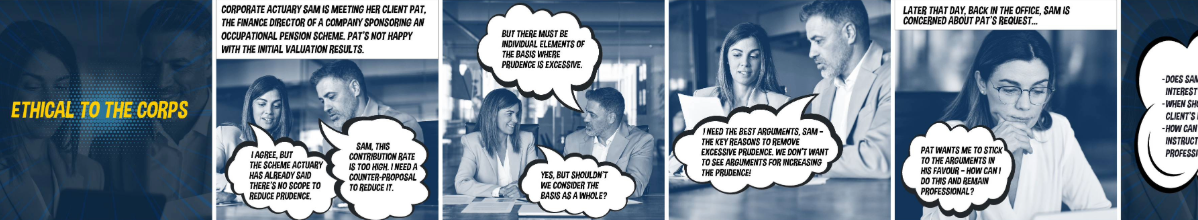

Does Sam have a conflict of interest?

The impartiality principle of the Actuaries’ Code (the Code) states that members “must ensure that their professional judgement is not compromised, and cannot reasonably be seen to be compromised, by bias, conflict of interest, or the undue influence of others.” Whilst it is a reasonable expectation that an actuary should act in their client’s best interests, and it’s also reasonable for a client to present their arguments and give instructions, this does not mean that actuaries should let their judgement be compromised if that client is attempting to influence unduly their professional decision.

A potential conflict of interest here is Sam’s wish to do what the client is requesting against what Sam might feel is the appropriate course of action. Sam might feel under pressure to make recommendations that reduce the level of prudence in the funding basis if she believes it would be lower than acceptable.

A key role of corporate pensions actuaries is likely to be supporting their clients (i.e. scheme sponsors) in negotiating a funding basis with the trustees. This is where corporate actuaries can add value for their clients. But Sam also has a responsibility to consider the wider impact of any advice given.

When should we challenge a client’s instruction?

Under the Speaking up principle of the Code, Members “should speak up if they believe, or have reasonable cause to believe, that a course of action is unethical or unlawful.”

The client’s request in this instance isn’t obviously unethical or unlawful—the finance director, Pat, is asking for a response in a negotiation that meets their business objective. However, as trusted professionals, actuaries should always consider the implications of following an instruction without challenge, particularly if it calls our own integrity into question. Therefore, if we have concerns about the implications of a client’s instruction then we should speak up.

A challenge need not be adversarial. We can state our position, our professional responsibilities, and our concerns. In many cases “speaking up” might merely mean asking for clarification and making the other party aware of the implications of their request.

As professionals, we have a duty to clarify and understand the instruction provided by the client. If an instruction is unclear, a wise course of action would be to state, in writing, your understanding of the brief and the course of action you intend to take.

In any case, if the client’s instruction is not in that client’s best interests, then you have a duty to raise your concerns with the client.

It is acceptable to decide not to act in circumstances where your professionalism would be compromised, for example if you had an unresolved conflict of interest.

How can Sam carry out Pat’s instructions while remaining professional?

The Scheme Actuary has already stated that there is no scope to reduce prudence. However, Sam is within her rights as a professional to take an independent view of the funding basis and challenge if her professional opinion is that there is in fact further scope to reduce the level of prudence.

In this case study, the responsibility for setting the funding basis will lie with the scheme’s trustees (i.e. the Scheme Actuary’s client) who must come to an agreement with the scheme sponsor (i.e. Sam’s client). Therefore, by challenging the Scheme Actuary’s proposal, Sam can argue that she is undertaking her duties as a professional.

The issue of concern here is the element of bias. Whilst there may be scope to challenge some individual elements of the funding basis, Sam should consider the basis as a whole when determining what is an acceptable degree of prudence. There may be some elements of the basis that are less prudent than others, but Sam believes the basis overall is at an acceptable level. If one element of the basis is, in Sam’s opinion, overly optimistic, she would be failing in her duty to the impartiality principle of the Code by deliberately ignoring it and focusing only on the elements that are overly prudent. Such “cherry picking” would not be in the spirit of negotiating for an acceptable overall level of prudence and would not be in the spirit of the Code.

Sam could offer to review the basis as a whole and present the client with a view on the overall degree of prudence. If Sam’s professional opinion is that there is scope to reduce the level of prudence, then Sam can focus on key basis elements to support this view and present this to Pat.